Kharkiv School of Photography: Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics

Part 3 - Contemporary 2

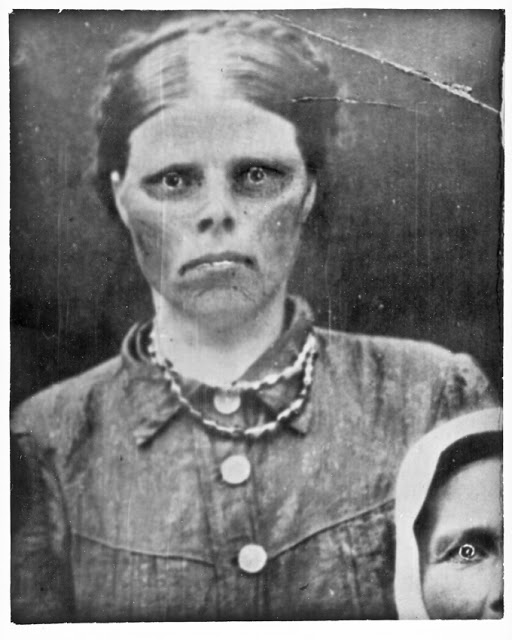

© Victor KOCHETOV, VINTAGE’ SERIES, 1970-91 [1977]

© Victor KOCHETOV, VINTAGE’ SERIES, 1970-91 [1977]

Rui Cepeda: Art entrepreneur, critic and analyst based in London. Rui has been leading art and cultural institutions and curating contemporary art events in diverse settings and mediums, such as the Triennial, in 2010 and 2013-2015, a cross-cultural festival bringing together contemporary art and gastronomy and local culture and heritage. Additionally he has been working, for several years, with various European cultural publications, either print or online, and has focused his writings on the ideological conflicts between geographies, the construction of subjectivities and on identity issues. Further to this, for two and a half years he held a weekly page about the market for contemporary art in a Portuguese newspaper. In 2014, Rui has started a Professional Doctorate in Arts and Cultural Management at the University of Manchester on Cultural Landscapes – Art as a Destination.

Rui Cepeda: Historical (Cultural) Dysfunction and Disarrays:

On the Kharkiv School of Photography

It is paradoxical to try to form an overview of an oeuvre that is culturally contextualized when I do not have the proximity or participative knowledge about it, only a critical distance from what has happened in one of the territories of what was once known as the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. All throughout its history Ukraine has been a piece that is part of a constantly fragmented mosaique, from which those territories (that are part of it) tend to represent on different moments through time Europe’s perspectives, or, in other instances, they share of a closer proximity to. It is within this context that its own individual history and outputs, like a school of thought/practice should be understood even when with a tangential approach to more Westerner political and cultural perspectives. The comments developed on the history of photography during the second half of the 20th century, while having an approach to the Kharkiv School of Photography (a visual approach that emerged and was constituted in the 1970s by a group of photographers, under the name of ‘Vremya’ (‘Time’), and which shared and proposed a vision distinct from that imposed by the Soviet official doctrine) will be helpful to find the convergences, divergences and tangencies within an artistic context from a Western perspective. A view that would make it easier to make sense of the time and space that encompasses us and can contribute in tracing down historical cultural dysfunctions and disarrays within a global context.

In the designated Western world, throughout the second half of the 20th century, the fear of a centralising communist socioeconomic structure being imposed over one in where the means of production were largely, or, entirely, privately owned and operated for profit hung around for more than four decades; as well as the persistent fear and the blind belief of an existing threat of nuclear warfare on a global scale. The socio-political context, throughout what is now known as the Cold War (between late 1940s and 1991), framed the outcome of images that were focused on a political ideology that suspended the continuation o being while holding time still. In contrast to images from the World War II period, those by Joe Rosenthal (1911-2006, US), Robert Capa (b. 1913, Hungary, d. 1954, Vietnam), Alfred Eisenstaedt (b. 1898, Germany, d. 1995, US), Yevgeny Khaldei (b. 1917, Ukraine, d. 1997, Russia), or Leni Reifenstahl (1902-2003, Germany), showed another reality: an ideological idea with models for the perfect environments or bodies, leading and charismatics figures posing while facing challenges. These new images—those about the American Dream and the Soviet Utopian Dream—had arisen from a necessity to stir doubt about the war’s goals and the deprivation soldiers had to endure in common. As international tensions continued to raise between the two political blocks in Europe - Western and Eastern – an anti-communist position, underlined by the love for pleasure and life (in certain parts of the Western world), leads the way; while, in others, it takes the form of a mad-hysteria (in the US throughout the 1950s with McCarthyism) underlined by a love for weapons and death; and, on another, by an antithesis, by the anti-capitalist position which, accordingly with the accounts of the day, was a reflection of what was happening on the other territorial extreme. Historically, the year of 1989 has become the landmark threshold for a transformation in discourses about established normative, after which we still had to go one more decade of rumours and side play.

© Eugeny Pavlov, The Violin Series, 1972

© Eugeny Pavlov, The Violin Series, 1972

If throughout the 60s and 70s artists, and other creative individuals, started to question the conditions of possibilities relating the institutional and cultural variables, in the following two decades they inquired upon those conditions but associated them instead with the social and economical variables. Since then, society at large has been going through the slow process of adjusting and synchronising the heavy machinery that governs and institutionalises the public sphere to the transient fashion of the moment, the coming of the body. Within a capitalist system the privatisation of the body—where we decide what we want to do with our own body—has become the first and most important privatisation. The body, in the last decades of the 20th century emancipated itself from the state, from religion, from the prevailing orders, and groups that govern contemporary society’s production, reproduction, and demand.

Coincidentally, all throughout the globe, a strong political movement with a post-colonial discourse started to gain relevance and importance in the geo-political arena: questions of cultural perception developed, and ways of viewing and of being viewed were reinvented. Meaning discourses—essentially cultural—through the voice of Léopold Sédar Senghor or Aimé Césaire culminated in the seventies.

The use given to history and historical narratives creates the impression of unity. A unique and singular state that is concerned with the idea that there are people destined to live in isolation, to live deprived, to live without, to live only one story drawn under vested interest (by the few), to a convenient mesmerizing destiny involving the whole; as Hobsbawn wrote, “traditions are invented by the sake of political discourses or ideologies.” In the midst of the Cold War, in the 1960s, the art community (artists, writers, and photographers) stopped having a stable field to look for references of belonging and being. Reality, as it was presented and lived throughout the 40s and 50s, was too muddy and illusory. It was shown as a perfect and ideal golden bowl, though, with cracks invisible to the naked eye. Throughout this historical period, photographers like the Swiss born Robert Frank (b. 1924, Zürich. Lived and worked in the USA), with his field project,The Americans (1958), or Diana Arbus (1923–1971, USA), with her photographic work on the deviant and marginal people of the U.S., used their camera to denote the shallowness of the leading institutional force in imposing controlling realities and dissatisfaction with a society that was being put up as the perfect state (the American Dream on one side of the Atlantic and the Socialist welfare state, on the other side). The Kharhiv School of Photography’s aesthetic principles share some of the same inquisitive criticality about the Soviet utopian dream of dysfunctions and disarrays. With a sturdy work they both engaged in capturing images that showed the bowl’s hidden cracks, and dystopian realities meanwhile influenced the development and the photographic approach taken by many other photographers and artists during the following decades—particularly in photo-social documentary. This emergence has implied redefinitions of the classic theory concerned only with social and economic variables, and requires one to also have a look at the institutional and cultural factors.

After the Second World War, artists did not know where to look and what to portrait without being linked to one of the existent socio-political ideologies ruling the discourses at the time—i.e. Capitalism, Socialism, or Communism. Although artists tend to represent contemporary society vices and virtues through their works, as usual, when not abiding with the ruling and normative discourses they are considered as dislocated and are put at the margins of society for society’s sake. If, with the 60s, a more neutral, aggressive and iconoclastic language emerged in the visual arts (Robert Rauschenberg, William Eggleston, Ed Ruscha, Bruce Nauman, just to name a few), in the following decade this approach was carried on further by the Düsseldorf School (Joseph Beuys, Gerhard Richter, Bernd & Hilla Becher, Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff, Thomas Demand, Thomas Struth, and Candida Höfer) in Germany, or David Hockney and John Davies in England, and Guy Le Querrec and Raymond Depardon in France. At this point, artists had started to look into one of the most prominent subject of works in art history—the body, the self, the being. Alternative realities had to be found or created: Helmut Newton’s (b. 1920, Germany, d. 2004, US) and Richard Avedon’s (1923-2004, US) bodies of work are counterexamples of work that was developed by Yevgeniy Pavlov, with The Violin (1972), or Yuri Rupin, withThe Sauna (1972). Psychedelic and dissociative discourses regarding one’s own place in the world started to converge on a global scale. In the 1980s, the work by Roman Pyatkovka (b. 1955, Ukraine) and Joel Peter Witkin (b. 1939, US) shared some technical resemblance when combining scratching the original film with the conceptual exploration of representations of the human body and flesh; or, a documentary approach to society in Christian Boltanski’s Chases School, 1986-1987 with poignant mementos referring to the Jewish Holocaust. Photographers played within a framework that contested theories of cultural imposition and perspective, while bringing a neutrality of the photographic object in where it means whatever it means to individual viewers.

© Roman Pyatkovka, Golodomor. Phantoms of the30s, 1990

© Roman Pyatkovka, Golodomor. Phantoms of the30s, 1990

Consequently, from the mid 1980s onward Conceptualism, as a movement in art, and Social Documentary (situated on the threshold between critical representation and factual reporting) were disseminated around the world. In some moments they converge and intertwine; in others, they are two completely distinguished sets of attitudes, observing the function of art in society and societal adaptations to specific political, economic, or cultural ideas. This is a condition that is quite visible in the images generated by the Kharkiv photographers who used photomontages, hand colouring, or a combination of the two techniques. In these works, the relationship between artist (photographer), artwork (photography) and audience is the focus. Boris Mikhailov’s (1983, Ukraine)photographic work, The Unfinished Dissertation (1984-1985), and Marcel Broodthaer’s (b. 1924, Belgium, d. 1976, Germany) installation, Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles (1968), interrelated those ideas and offered an institutional critique. In particular, a criticality related with those various institutions that drive society at large and, more specifically, the work of art institutions, such as galleries and museum, and the conventions in society and art.

From a critique that unravelled, uncovered and critically re-examined (throughout the 60s, 70s and 80s) the convincing logics and operations of the post-war truths (claimed since 1945 until late 1960s), the criticality brought upon by the 90s onwards aims to recognise the limitations of one’s thoughts. While making visible historical and social constructed boundaries between the ‘we’ and the ‘other’; between what is from the inside and from the outside; what is from the public and private sphere. In where “one does not learn something new until one unlearns something old, otherwise one is simply adding information rather than rethinking a structure.” When one would expect the homogenization of discourses, the array of different cultural values and expressions has become overwhelming. Photo-social documentary or social-realist photographers, like Elliott Erwitt (b. 1928, France), Gilles Peress (b. 1946, France), Chris Killip (b.1964, UK), and Antoine D’Agata (b. 1961, France), create images documenting fear, desire, drugs, and sex, in the tradition of Nobuyoshi Araki (b. 1940, Japan) or Nan Goldin (b. 1953, US). All are focused on somatic needs, as opposed to the needs of the spirit or other non-physical entities like the State and nationalistic ideologies.

Since the end of the Second World War, there has been a prevalent hegemony of discourses associated with the political left which thinks through and relates what is happening both in the private domain and public sphere to economic and social variables in the media, in political parties, in culture, and in the arts. In particular, because those political regimes that were deposed in Western Europe (Germany, Italy, Spain, and Portugal) were associated with political discourses imposed by a particular authoritarian political right--that which thinks through and relates those things happening to cultural and institutional variables. Since then, the West has been living an alternative of the same left. Ukraine, in contrast, has lived under the dictatorship of the left for several decades. The difference between the two lies in the reality that some political discourses are closer to the left than others. The counterculture/social revolution of the 1960s that brought into the main arena a discourse about the body (epitomised by the hippies’ countercultural movement in the U.S. during the mid-1960s and the French sexual revolution of 1968, in Western Europe), and, even more, with the advent of the Internet, communication of ideas and access to information went beyond political parties, institutional impositions, and national discourses; beyond the Utopian projects and leading toward the body, the self, and thebeing. With Internet and digital information has emerged a more conjectural language, knowledgeable attitude, and participative audience that both conjure the intangible element brought by the Internet and the bodily needs of the being and of the flesh.

© Vladimir Starko, Untitled, 1986

© Vladimir Starko, Untitled, 1986

Consequently, migration on a global scape along with this increasingly fast means of communication means that artists from the most recondite places in the world can have their voices heard. An on-going negotiation of cultural difference exists in our everyday lives; social changes occur on both sides of the communication process. New predications take place! New connections are being made and created way beyond conservative views or utopian ideals.

Before there were pixels deluging the world, artists introduced new topics on the discourses that challenged those that were by far already established. They pointed to other relational structures of possibilities in art history and in social relations, and to the distance between what was from the private domain and public sphere. Take, for instance, The Finest Art on Water (2011) by German artist Christian Jankowski as a culmination of the discourses used by artists in the 1960s, testing the boundaries between high art and mass-culture, and following a Pop tradition, which explores the concept of what is banal and mundane as characterized by the English artist Richard Hamilton (1922-2011). In the meantime, other contemporary artists, such as Francis Alÿs (b. 1958, Belgium), Rirkrit Tiravanija (b. 1961, Argentina), Pierre Huyghe (b. 1962, France), Philippe Parreno (b 1964, Algeria), and Anri Sala (b. 1974, Albania), have been focusing their discourses on perversion, obsession, horror, fear, trash, and the pain resulting from controlling forces. Through their work, these artists have been underlining a position in a social-cultural body that is filled with sensations, making us laugh, and at the same time, educating us about the diversity of discourses, false hegemony, and an obnoxious, coked-up version of supposedly extra-real reality where objects have feelings without us.

By intersecting the conceptual and realist frameworks, the contemporary artist (photographer) asks its audience to rethink the structure of power imposition, which have previously separated artistic disciplines/practices. They create sceneries, montages, and construct apparatus, objects, and technical images as subjects. From sculpture to painting, photography to video and digitally-based art forms, contemporary artists are dealing with society’s non-visible controlling forces, which take the shape of the State, Church, economy, sexuality, images, and drugs. A change, due in part, to the realization by society at large and photographers in particular, that the medium’s power for deception is built on a belief of its documentary verity, its inability not to pay equal attention to all that has come through the camera’s aperture, as was expressed by the English art critic, John Berger (b. 1926), in his 1972 seminal BBC four-part series and accompanying book, Ways of Seeing. The work by the American conceptual artist, Barbara Kruger (b. 1945, US), incorporates and addresses that concurrent bigotry like order-words. She plays between what is from strange-familiar places through the combination of image and text, and the use of a directed language and pronouns such as “I,” “you,” “we,” “they,” and “your,” whilst underling their iconic social position in the social-cultural body. Fear as a feeling that has been explored, in a subliminal way by the different political power institutions; those who have been governing the distinctive geo-cultures around the globe, since after the Second World War.

© Oleg Malevany, 'Dance', 1980

© Oleg Malevany, 'Dance', 1980

Photography’s verisimilitude and reliable visual reproduction of what “is,” by nature makes it the most neutral vision in cultural production—a means to democratise knowledge derived from sense-experience. Nonetheless, throughout its history, photography democratic neutrality and objectivity has been questioned on multiple levels: from the interpretation of ideas disclosed by images to humankind’s technological achievements. However, photography processes and records images independently of the physical ability or mental intentions of who takes the picture. It draws from nature through means of light. It is the ability and intentions of those who take the pictures, the photographers, which should be contested. An image is fixed on a tangible support by a technological process, being those, a piece of metal or paper, cellulose acetate or electronic material. Most importantly, however, is that photography began to alter the human relationship with memory—the neuropsychological process of communicating encoded, stored, and retrieved information. It has become a physical and chemical stimulus, a second memory, storing information over periods of time in an objective, effortless, and independent way. The sense of being there, of a personal encounter, connected individual experiences through images produced as genuinely akin to actual experiences, and, moreover, the ideal of democratic access to information.

Present day focus on photographers and artists might have started with a message sent between UCLA and Stanford University in 1969. However, two decades later, the Internet has invaded our homes, establishing itself as its rightful owner, while mediating our deepest secrets and becoming our artificial confidant. Through Facebook, Instagram, Tumblr, present-day society shares its most intimate thoughts as recycled images. Living a simulacrum in which society is more concerned with maintaining and reproducing an illusion, at any cost, rather than living reality. Average people engage in a mass reproduction swept along the stream of images provided by those apps, appropriating them, while adding something to their understanding. Nonetheless, the dichotomy here, with the Kharkiv School of Photography, is their found freedom and how this school of thought/practice has been occupying and existing within this new condition of possibilities. After 1989, with the disintegration of the USSR into nation-states, the playing field that was previously forbidden—for instance, images of naked people, particularly woman, which could have been considered representations of political independence from a centralised state — have become a fashionable obsession; whereas, before 1989, it was a contested playing field about the cultural dysfunctions and disarrays brought by socio-political imposition and institutional idealisation. This does not mean that photographers prompting Kharkiv thoughts continued to rematerialize the world with only sexual and erotic imagery. Valdyslav Krasnoshchok (b. 1980) and Sergiy Lebedynskyy (b. 1982), who founded the ‘Shilo’ group in 2010 with Vadym Trykoz (b. 1984), visually reconsider the heritage of both the Kharkiv School of Photography and Josef Koudelka’s Prague Spring photographs; and Roman Minin’s (b. 1981) participatory art, integrating the masses, links to the practices of such artists as Rafael Lozano-Hemmer (b. 1967, Mexico), and the Mexican muralists, David Alfaro Siqueiros (b. 1896 – d. 1974), Diego Rivera (b. 1886 – d. 1957), and Jose Clemente Orozco (b. 1883 – d. 1949), whose works attempted to educate the masses through large-scale interventions on building facades. The Kharkiv photographic works are a clear encouragement and example of paralleling Western artists interested in the socio-cultural inconsistencies of how the body is and occupies existing space. Some photographers continue to play with the social realism that characterised previous generations, while others explore relationships and existing possibilities between what is conceptual and what is realist.

While photography is used in the same way—as a mean of, and for, social and political comment—what distinguishes the different sides discussed here (the Western perspective from the Kharkiv School of Photography) is the playing field. In the latter, the realistic depiction of contemporary life as it was under a more constrained freedom is still the playing ground; in the former, the playing field has become those virtual platforms that exist as memory aids, substituting the body, the being, and the self. With Internet connecting realities and feelings, and the array of digital supports flooding the globe, the first thought that comes into my mind is that information technology has substituted our memory, skills, and knowledge like prostheses; like the idea of Noah’s Ark as being a big transitional USB pen packed with data, 0’s and 1’s; or, being an aesthetic white cube, in which data is stored and displayed for buyers, i.e. collectors or investment funding trusts, just like the data storage centre are immaculate spaces free of that horrifying external and timeless thing that dust is. The body is all that remains to us of the real, with its still unique capacity to suffer, enjoy, feel.

The second significant idea that derives from the practice of present day artists is aimed towards works functioning as physical archives for non-physical images, works existing only on the Internet (Google search or Facebook albums). Those found images or, instead, images that are taken from that archive (Internet) contaminated by non-visible metadata. This creates narratives and dissociates/associates images that are mediated by the archive itself; or, what follows the confrontation of and the creation of new subjectivities, as those images that are presented by the photographer Mishka Henner (b. 1976, Belgium) when reframing depictions taken from Google Earth. All photographer play with photography and the act of not to take photographs as well, instead of looking to ‘find the differences’ between two “equal” images. It is where we have to connect what relates and brings together what seem to be different in images; it is where we have to connect the equal to be at rest – to be hegemonic. Whilst the whole idea is to establish an alternate to the dominant archive and interfere in how we educate, set our gaze. But, as I wrote at the beginning, this is just one side of the discourse about a school of thought and practice.

Bibliography:

Berger, J. (2008) Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Classics.

Hobsbawn, E. and Ranger, T. (Ed.) (2012) The Invention of Tradition. Reissue edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Latour, Bruno (2001) ‘What is Iconoclash? Or Is there a world beyond the image war?’, Bruno-Latour.org’s website</i [Online] [Accessed] Available from http://www.bruno-latour.fr/node/64

Rogoff, Irit (2006) ‘Irit Rogoff: What is a Theorist?’, Kein.org [Online] [Accessed February 26th 2013] Available from http://www.kein.org/node/62

Warner Marien, M. (2002) Photography: A Cultural History. London: Laurence King Publishing

1. A series dedicated to the Great Famine of 1932 – 1933 in Ukraine, the Holodomor (‘killing by hunger’), when million of people were forced to starve to death by Josef Stalin, with a death toll ranging from 1.8 to 12 million people. A parallel can be made with the Great Chinese Famine, from 1958 to 1962, in where China experienced a monumental famine that killed at least 45 million people due to essential two causes: natural disaster and communist polices.

2. In 1957, Hamilton listed the characteristics of Pop Art, as: popular (designed for a mass audience) transient (short-term solution), expandable (easily forgotten), low cost, mass produced, young (aimed at youth), witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, big business.