Livio Senigalliesi: Imagine No Heaven

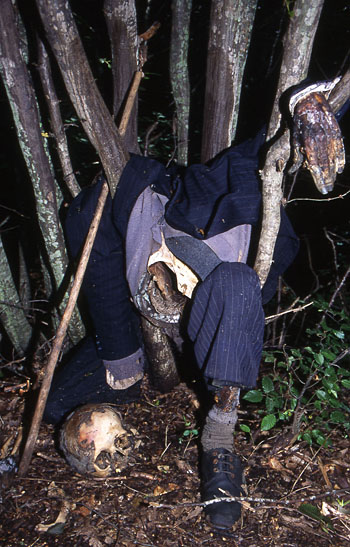

© Livio Senigalliesi, Croazia Vukovar 1992

© Livio Senigalliesi, Croazia Vukovar 1992

Connecting what one sees to what one understands

VASA exhibitions include the work of various photographers and filmmakers who employ the lens as a vehicle for social commentary and what traditionally is referred to as documentary or reportage – the camera understood as a witness.

“I can’t conceal my despair in the face of such suffering. Geared up by the desire to document this human tragedy, I kept taking pictures, always in the most respectful way towards the victims, but somehow I felt restrained. Compassion was overwhelmingly stronger than my sense of duty. Those pictures had to be taken but more often than not I gave in to long enforced breaks, with tears streaming down my face.”

... Livio Senigalliesi

The comment above by Livio Senigalliesi challenges the notion of the impartial witness or the resulting report to a narrative grounded on emotion and empathy. A narrative far removed from objectivity and “Truth”. (I use the “T” to denote “a” truth over multiple truths.) The range of images included in this exhibition emerged out of a tradition of photojournalism, requesting our consideration of the human on both sides of the lens. I say this fully knowing that “all” photographs point to both sides of the lens; the mind behind it and the objects in front of it.

Livio is a war photographer. This separates him from a photographer who is assigned to cover cultural and news worthy events. As he explains in his text and interviews included in this exhibit, he places his well being, his life on the line every time he ventures into a conflict zone, points his camera or talks to a person at the wrong moment. Carrying press identification was no guarantee that he was protected or free to record what was before him. It was not a given that the people, soldiers and civilians photographed would accept him or trust him. At any point he could be captured, tortured or killed. Yet, he had a job to bring back to his publisher images and stories about the unfolding of events he witnessed. This witnessing, being in the presence of, refers to the human factor of any witness. His photographs, the representations he produces, go beyond the mere recording to points of decisions that subjectively recognizing the metaphorical or emblematic nature of what stands before him – the representation of a reality. Standing before him, it is not what he sees but what he understands. There is a difference between “seeing” and “understanding”. To see is to notate, to understand is to give meaning.

Livio is a war photographer. This separates him from a photographer who is assigned to cover cultural and news worthy events. As he explains in his text and interviews included in this exhibit, he places his well being, his life on the line every time he ventures into a conflict zone, points his camera or talks to a person at the wrong moment. Carrying press identification was no guarantee that he was protected or free to record what was before him. It was not a given that the people, soldiers and civilians photographed would accept him or trust him. At any point he could be captured, tortured or killed. Yet, he had a job to bring back to his publisher images and stories about the unfolding of events he witnessed. This witnessing, being in the presence of, refers to the human factor of any witness. His photographs, the representations he produces, go beyond the mere recording to points of decisions that subjectively recognizing the metaphorical or emblematic nature of what stands before him – the representation of a reality. Standing before him, it is not what he sees but what he understands. There is a difference between “seeing” and “understanding”. To see is to notate, to understand is to give meaning.

At no time does Livio assume the camera is free of a contextual framework, detached from the mind behind it. The camera that records data, embedded on chip or film, is not separated from the mind that points it. The photographer is not removed from the camera she uses, the lens collecting the light, the edges of the frame, her history, and the historical cultural framework of image making. The decision to stand where one does is not by chance but by one’s history. We live in a social, political, and economic world, gaining its meaning from intersecting historical contexts. The resulting image of the metaphorical click signifies an intelligence that is shaped by a history, intention, and human interest. The challenge I would suggest is connecting what one sees to what one understands.

The photographer as a witness does not create an empirical report on the world, but authors a subjective story told through different voices. These voices include the fluidity of events, the decisions made by the photographer, the selection by an editor, the publisher and finally the viewer (reader).

Photographs and films (video) are made as the result of decisions, not decisive moments. The decision to point the camera or stand in a place at a particular time, are not made by a neutral observer or machine, but by an intelligence, acting on the world from a point of interest. There never was or will be disinterested or non-contextualized images. Each image (or set of images) is the result of an intention and an understanding of what an image looks like and what the intended function is or will be. Representations are formed around existing codifications, an existing language needed for the construction of meaning. For the readers of “Imagine No Heaven” (all viewers read the image(s) as a text produced for consumption. A film, as is a photograph, a poem, or painting, is created to be at some level experienced.), significance is constructed through the reader’s own historical placement, one that is biased as is the image and the image-maker. In this sense the reader of the text is a witness, a witness to the biases of the medium of photography, the image-maker, the curator, and VASA Exhibitions. (I refer to VASA Exhibitions because they are the collective result of curators and editorial policy; decisions and intentions.) If one views an image(s) or a film, and does not reflect upon the experience from both sides of its frame/lens, one’s relationship to the image, the point is lost. Of course it can be argued that in the act of “meaning making”, the viewer is reflecting and constructing the experience herself. No experience exists outside a viewer.

Photographs and films (video) are made as the result of decisions, not decisive moments. The decision to point the camera or stand in a place at a particular time, are not made by a neutral observer or machine, but by an intelligence, acting on the world from a point of interest. There never was or will be disinterested or non-contextualized images. Each image (or set of images) is the result of an intention and an understanding of what an image looks like and what the intended function is or will be. Representations are formed around existing codifications, an existing language needed for the construction of meaning. For the readers of “Imagine No Heaven” (all viewers read the image(s) as a text produced for consumption. A film, as is a photograph, a poem, or painting, is created to be at some level experienced.), significance is constructed through the reader’s own historical placement, one that is biased as is the image and the image-maker. In this sense the reader of the text is a witness, a witness to the biases of the medium of photography, the image-maker, the curator, and VASA Exhibitions. (I refer to VASA Exhibitions because they are the collective result of curators and editorial policy; decisions and intentions.) If one views an image(s) or a film, and does not reflect upon the experience from both sides of its frame/lens, one’s relationship to the image, the point is lost. Of course it can be argued that in the act of “meaning making”, the viewer is reflecting and constructing the experience herself. No experience exists outside a viewer.

When Livio writes “… Those pictures had to be taken but more often than not I gave in to long enforced breaks, with tears streaming down my face.” he is referencing more than making an image for an assignment and a publication. Livio confronts a projection of “self” on what is in front of him. He recognizes more than a person to be objectified but a human, like himself, alive, living a life. As a photographer he wants to speak, to make a comment about himself.

Text and images by Livio Senigalliesi providers the viewer (who sits in a safe seat) an overview of a life committed to people, the image, reportage and representation. If anything, as the above quote refers, this exhibition offers us a portal into the mind and vision of a photojournalist committed to telling a humanist story, not just a report, but a story. It is his story, one that we can only abstractly experience through his images and words. In the end, as readers of his text, we create our own stories, our own meanings. From this perspective, the work is fluid within the edges of our own experiences and perspectives – our lives.

All images © Livio Senigalliesi

Upper image: Kosovo Resti Umani 1999

Bottom image: Iraq Ramadi 2006

© Roberto Muffoletto, 2020