Kharkiv School of Photography: Soviet Censorship to New Aesthetics

1970-1980s

Tatiana Pavlova: Late 1960s to 1980s -- The Vremya Group’s Time

Unknown author. Kharkiv, end of 1930s

Unknown author. Kharkiv, end of 1930s

The crackdown on the Ukrainian avant-garde movement, a movement that thrived in Kharkiv in the 1920s, came to be known as Executed Renaissance. One of the avant-garde’s movement’s high points was Constructivist photography. By the 1930s, any efforts at experimenting with the medium had been extinguished. The strengthening “totalitarian discourse” spelled death for independent Ukrainian photography, with photographers now forced to “document” a fictionalized version of reality. In the 1930s, the future-oriented Constructivist dynamic of Ukrainian photography was replaced with measured narratives, the bold camera angles abandoned in favor of classic ones. Shooting from high vantage points, popular in the 1920s for the unusual angles it allowed, was pronounced taboo. One had to obtain a special permit to shoot from above the third floor. Forbidden subjects also included railways and train stations, demonstrations, and Communist party buildings. Photography’s main function was to service Utopian ideological constructs. (image left: © Vasil Yermilov. Selfportrait with a Bicycle Mirror, end of the 1930's)

The rapid curtailing of public liberties in the 1930s put the development of Ukrainian photography on hold. The last avant-garde periodical, Kharkiv-published Nova Generatsiya (“New Generation”) magazine, was shut down in 1931. It was in Nova Generatsiya that Kazimir Malevich’s key theoretical works first saw publication – in 1929- when the artist had already fallen out of favor with the authorities. That same year, the theory and practice of Ukrainian photography suffered a loss in the death of Leonyd Skrypnyk, a talented photo theorist whose essays had been regularly featured in Nova Generatsiya. The magazine’s editor, a Futurist poet Mykhail Semenko, was executed in 1937. The magazine’s archives have never been recovered, and nothing is known about the fate of the art editor, the extraordinarily gifted Constructivist photographer Dan Sotnyk. The totalitarian regime’s growing oppression of art, culture, and public life in general put the brakes not only on photographic experiments but on any artistic progress whatsoever. Strict censorship and unprecedentedly brutal punishments made photography a dangerous pursuit.

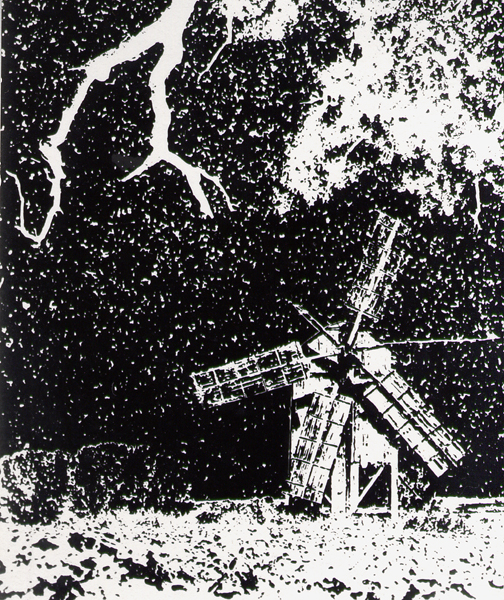

© German Drukov. Devil's Windmill, early 1970's

Consequently, while in other Eastern bloc countries it did not take long to reestablish their tradition – for example, Fotografia magazine in Poland – began publication as early as 1948 – in Ukraine, photo clubs only started reappearing during the Khrushchev Thaw (The Khrushchev period, late 1950s to 1968, witnessed the loosening of party control over social freedoms.). 1960 saw the foundation of the Lviv Photo Club (“in a total void,” as its leader Roman Baran put it), which, although praised by contemporaries for its liberal creative policies, was still a far cry from the national traditions worthy of Lviv’s intellectual elite. In 1950, a number of former Ukrainian Photo Society members restored it as part of the Literary & Art Club in New York. Meanwhile, back in the Soviet Union, the relatively less restrictive public climate of the Thaw led to the popularity of the club’s movement, creating new cultural avenues to be explored by “amateur art photography groups.” The Kharkiv Photo Club was founded in the early 1960s. Kharkiv’s amateur photography scene thrived thanks in large part to the availability of locally produced FED cameras. Officially recognized photo clubs were akin to professional unions, providing photographers with the infrastructure already offered to artists, musicians, and writers by their respective Unions. The Kharkiv Photo Club was established as a photography section at the famous Cinema Lovers’ Club, a haven for local intellectuals where they could discuss films and meet such people as, for example, the famous movie director Andrei Tarkovsky. Naturally, such organizations had their share of government informants whose job it was to report any signs of political disloyalty. The Kharkiv Photo Club was no exception in this respect, any ideologically suspect gestures by its members drew an immediate response from the KGB. To get in trouble, one did not necessarily have to be a political freethinker: even showing an interest toward photographic developments in the West was sufficient.

© German Drukov, Untitled, 1969

From the late 1950s, European photography was concerned with seeking out an alternative to the classical approach, treading in the footsteps of surrealist and abstract artists. Photographers would play with shapes and optical illusions, utilizing odd light-and-shade effects, geometric forms and lines captured on film. The new wave that swept through post-Stalin Soviet culture could not help but influence Ukrainian photography, where industrial subject matter now gained popularity along with the idea of capturing the laconic plastic shape. The search for laconicism sparked a renewed interest toward photomontage, a technique which became prevalent in Ukrainian photography at the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s. Back in the 1920s, which had come to represent the golden age of montage and collage, this practice was validated by a complex historical argument that drew a parallel between the photographic montage and the social change brought about by World War I. The new wave of montage also had much to do with postwar transformation. At the time, German Drukov, the Kharkiv Photo Club’s leader, was into photo-graphics. Drukov’s dynamic collages paid homage to the 1920s photographic avant-garde, establishing a new link with the movement that seemed forever banished from the Soviet cultural monolith, testifying, albeit in nontraditional ways, to its lasting legacy. With their typically high contrast, Drukov’s works emphasized the graphic quality of the image, accentuating rhythmic interplay, laying bare the very structure – and, sometimes verging on abstract. But his structural experiments did not resonate with younger photographers. During the Thaw, similar photo clubs sprang up in other large cities all over Ukraine. But it was within the Kharkiv Club that a prominent nonconformist movement began, perhaps most famously personified by Boris Mikhailov.

The 1970s

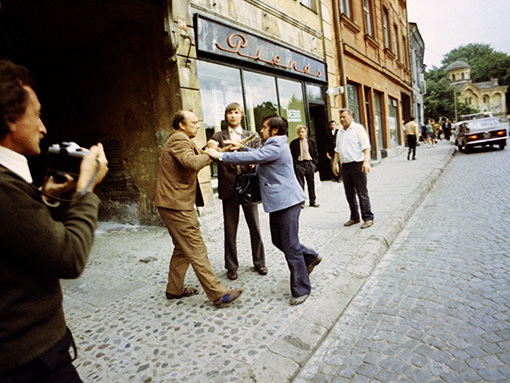

Rupin, Mikhailov and Pavlov at the public discussion of their closed exhibition at “The House of Scientists”,

Rupin, Mikhailov and Pavlov at the public discussion of their closed exhibition at “The House of Scientists”,

Kharkiv, 1983. Pavlov is impersonating a highbrow scientist.

Many among the new generation of photographers who had an impressive start in the 1960s were later forced to frequently compromise while still working at the margins of the official art movement. It was only natural for them to seek out kindred spirits. It was in the youth-dominated atmosphere of the Photo Club that they felt most at home, becoming, over time, its core membership. It was a place they came to for professional support, which was essential for photographers at the time because their chosen field of work required familiarity with complex technologies. The Club brought together for the first time the future founders of the Vremya (“Time”) art collective.

© Juri Rupin, 1970's, Mikhailov is taking a picture of a street scene

In 1971, the young and ambitious Jury Rupin and Eugeny Pavlov approached a number of prospective Club members with the idea of forming a collective; they were Boris Mikhailov, Oleg Malevany, Gennady Tubalev, Aleksandr Suprun, and Aleksandr Sitnichenko (Anatoly Makienko joined some eighteen months later) (1) Jury Rupin was the group’s main driving force: Boris Mikhailov went so far as to suggest that Vremya ceased to exist once Rupin abandoned photography in late 1980’s. The collective came to share a common declaration, what they called the “blow theory” – an idea that their photos should “punch the viewer in the face.” It is exactly this essential property of any outstanding photography that Roland Barthes would identify as punctum (“puncture”) almost a decade later in his seminal Camera Lucida. (image:

© Gennady Tubalev. A Bride, late 1960's

The Vremya Group images presented a new way of looking at Ukrainian reality. It is this Kharkiv era, when “people would come from Moscow and Kyiv, rise up from the seas and descend from the Cordilleras to hang around in the violet twilight of Rymarska Street (3) , that has been so vividly depicted in the autobiographical novels of Vladimir Landkof, Eduard Limonov.(4) This was the period that gave birth to a radically new school of photography that was to become world-famous.

The Vremya Group images presented a new way of looking at Ukrainian reality. It is this Kharkiv era, when “people would come from Moscow and Kyiv, rise up from the seas and descend from the Cordilleras to hang around in the violet twilight of Rymarska Street (3) , that has been so vividly depicted in the autobiographical novels of Vladimir Landkof, Eduard Limonov.(4) This was the period that gave birth to a radically new school of photography that was to become world-famous.

(image right: © Boris Mikhailov. Susie and Others, 1960’s – 1970’s)

The 21st-century hindsight makes it difficult to grasp just how audacious the group’s name, “Time,” actually was. Essentially, it was an effective way of signifying “contemporary” while bypassing any censorship. The group used two different images to mark their works, one bearing the group’s name and another depicting an owl. Such Boschian transformation of a sunny Pegasus into a night bird is a natural survival tactic for those forced to exist underground (a smart appeal to the goddess of wisdom when dealing with “art critics in plainclothes”). The collective had had its share of trouble typical for all freethinking artists in the Soviet Union, from excessive alcohol consumption and police raids to punitive psychiatry, KGB surveillance, and prison camps.

Boris Mikhailov, the most mature of the group, was also perhaps the most prominent photographer. A charismatic man, he attracted some and repelled others. Back then he could not even show all his work at the Photo Club gatherings. Each new photograph was a blow against the monolith of Soviet aesthetics—only shown to his Photo Club inner circle, it was nonetheless always a bombshell, a slap to the face of the Club’s art council. With many of his earlier shots of the late 1960s, it took Mikhailov himself a long time to make sense of them, when he arranged them into conceptual series years later. Later still came the necessary verbal commentary. Back in the sixties, however, it was the footage itself that held the most value, shot as it was within a completely new ideological framework. Mikhailov’s idea, still vague at the outset, was to document personal emotional experiences. At the turn of the decade, Mikhailov created the series Horizontal Pictures, Vertical Calendars (1968), Suzie and Others (1960s–1970s), The Red Series and Overlays (1968–1975). The latter one used the technique “sandwiching” slides one over another. Mikhailov claims the technique was invented in Kharkiv. What he probably means is that, while the method itself was not new, it nevertheless found its most widespread use in Kharkiv, with startlingly new results.

Boris Mikhailov, the most mature of the group, was also perhaps the most prominent photographer. A charismatic man, he attracted some and repelled others. Back then he could not even show all his work at the Photo Club gatherings. Each new photograph was a blow against the monolith of Soviet aesthetics—only shown to his Photo Club inner circle, it was nonetheless always a bombshell, a slap to the face of the Club’s art council. With many of his earlier shots of the late 1960s, it took Mikhailov himself a long time to make sense of them, when he arranged them into conceptual series years later. Later still came the necessary verbal commentary. Back in the sixties, however, it was the footage itself that held the most value, shot as it was within a completely new ideological framework. Mikhailov’s idea, still vague at the outset, was to document personal emotional experiences. At the turn of the decade, Mikhailov created the series Horizontal Pictures, Vertical Calendars (1968), Suzie and Others (1960s–1970s), The Red Series and Overlays (1968–1975). The latter one used the technique “sandwiching” slides one over another. Mikhailov claims the technique was invented in Kharkiv. What he probably means is that, while the method itself was not new, it nevertheless found its most widespread use in Kharkiv, with startlingly new results.

Image © Gennady Tubalev. Untitled, early 1970's

The new generation of Ukrainian photographers was struggling to find a way of free expression that had not been already claimed by some movement or other. They reclaimed their environment by conceptualizing it anew, and it was Boris Mikhailov who led the charge. A sort of carnival atmosphere pervades his absurd slide pairings that seem to defy logic and common sense: a nude female body overlaid with a courtyard of some tenement building, a carpet waiting to be cleaned lying in the snow; a construction site superimposed on yet another naked body so that it becomes centered around the buttocks – according to Mikhailov, this means “the construction isn’t going too well.”

(image right: © Boris Mikhailov. Calendars, 1968 – 1980)

Kharkiv photography displays a merging of the documentary and the creative formats. Throughout the 1970s–1980s, the landscape becomes more detailed, and the urban environment comes to be defined by what James Joyce called “street furniture.” Another prominent feature is the “metallization” of nature, the kind Walter Benjamin observed in Futurist art. Boris Mikhailov’s own caption to one of his pictures says, “I can’t shoot a landscape devoid of metal.”

The documentary aspect of Mikhailov’s photos is rather subjective, as he freely admitted himself on numerous occasions. His interest in this aspect of photography was already evident in his late-1960s series (The Engineers, Suzie and Others). Mikhailov’s unusual approach to documentary photography is to choose the less sharp, less composed of two shots, since it produces a more immediate impression of realness. Far from being taken under “academic” conditions, a shot like that was obviously made on the fly, with no time for focusing the camera. This is why V. Tupitsin views Mikhailov’s work as a terminus for the “deconstructivist odyssey” embarked upon by the Moscow artists V. Komar and A. Melamid. These artists are directly referenced in the Sots Art series (1975–1986). Such intertextuality is common in Mikhailov’s work of the 1970s–1980s. For example, the b&w series Fours (1982–1983) references Vyacheslav Tarnovetsky, who popularized the eponymous method of saving photographic paper by placing four shots per sheet. Mikhailov, however, is more interested in the relationships arising among the four pictures.

(above image: © Boris Mikhailov. Fours, 1982 - 1983)

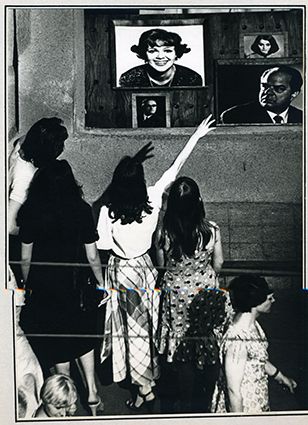

Boris Mikhailov’s famous series Luriki (1971–1985) uses anonymous photographs. By revealing their quasi-folk language, Mikhailov channels it into self-revelation. Giving a voice to the underclass highlighted the relative nature of life values, which became the focus of Kharkiv photography. In later work Mikhailov uses the same subject matter to project a personified fear of people on the brink of poverty, people living “on the edge” (the body of work was entitled “Case Study”). It is no secret that this is a common esthetic in contemporary culture. Back in the 1930s, Antonin Artaud defended his Theatre of Cruelty as a natural need for tension, controversy, and conflict. For the Soviet reality, however, such an approach bordered on dissention, making life difficult for the photographer. Mikhailov views society’s outcasts in an unexpectedly poetic light, as if discovering them anew. This is a result of the marginalized existentialist experience of Kharkiv’s art elite. (Above imnage: © Boris Mikhailov Luriki. 1971 - 1985)

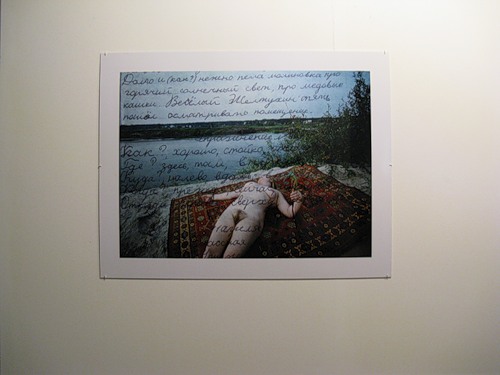

At the beginning of the 1980s, Mikhailov introduced the genre of “artist’s book” (livre d’artiste), expanding the language of contemporary photography in his Viscosity, Crimean Snobbism (both 1982), and Unfinished Dissertation (1985). He employs autobiographical touches to create a series of snapshots in a “book,” a special artistic technique which is quite deliberate. Using this type of narration, deeply rooted in European culture, emphasizes his being a part of the general cultural process. An artist’s book’s message is shared between the pictures and the texts. As Barthes notes in his Camera Lucida, “writing and pictures…do not call upon the same type of consciousness…pictures, to be sure, are more imperative than writing, they impose meaning at one stroke, without analyzing or diluting it.” (5)

© Boris Mikhailov. Susie and Others, 1960 ’s – 1970's

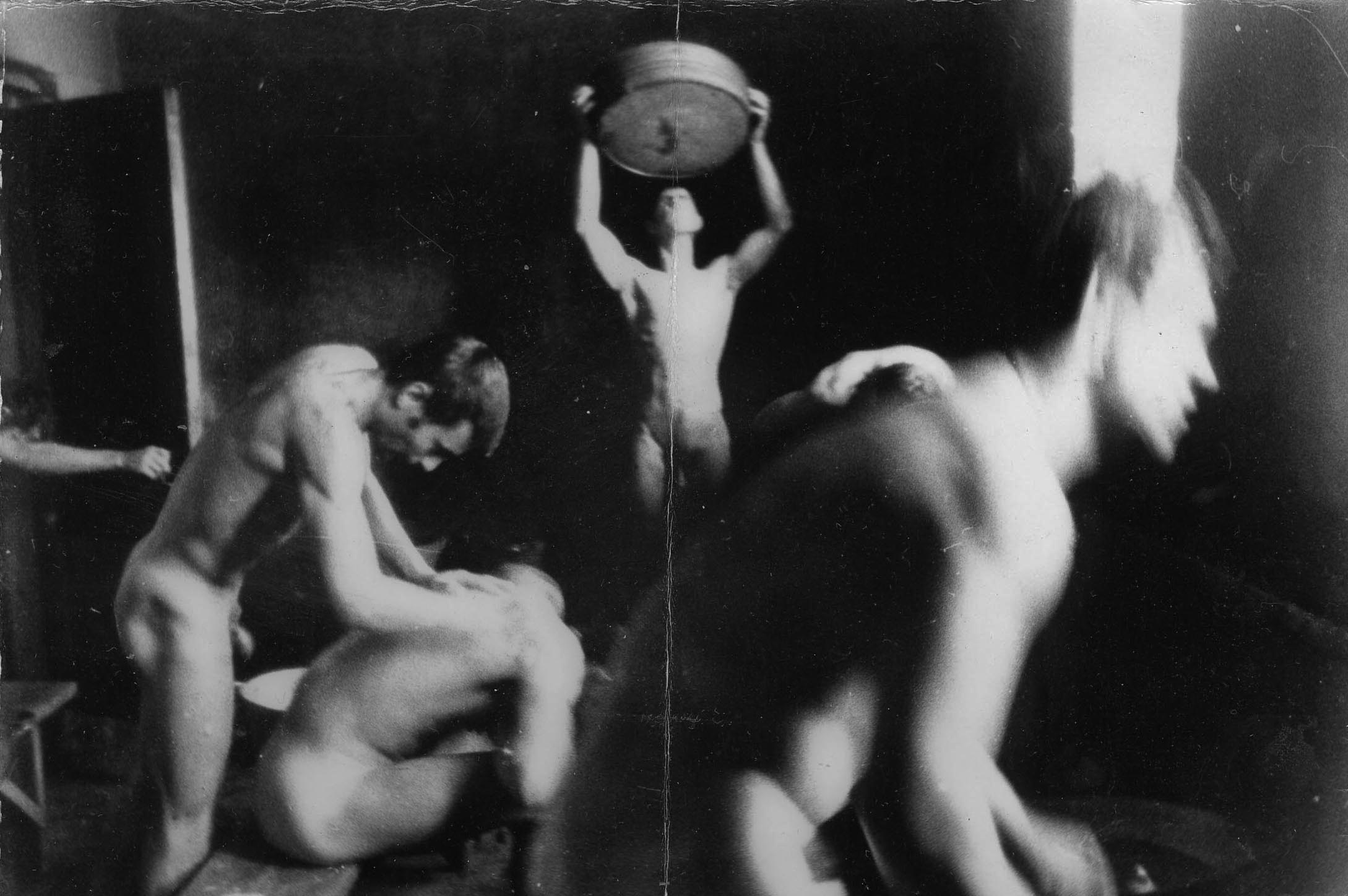

Only when one considers the wider context of de-feminization and de-masculinization promulgated by the Soviet regime can one appreciate the primacy of the nude female body advocated by Vremya as one of the “blow theory’s” fundamental aspects. Reclaiming the female in photographic art was also an act of rebellion against both the explicit and the tacit castration of art and the Soviet society as a whole. By accentuating the buttocks and other deemed “indecent” parts of the woman’s body, the artists vicariously emphasized the male force and the active male libido. This aspect of Kharkiv photography is evident in Boris Mikhailov’s pictures that would make up his series Suzie and Others. Pornography was a criminal offense in the Soviet Union, and the legal definition was so vague that any photographer who took a nude picture could be easily charged as authorities saw fit. This was one of the many ways the government used to keep the people in check by arbitrarily assigning guilt. Keeping all this in mind, it is easy to see what a gesture of defiance it must have been when it was the nude male body that entered the picture. Prohibiting the photographing of nude models “in inappropriate circumstances,” i.e. outside of a bathhouse, created a legal loophole that was used by Jury Rupin in his impressive Sauna (1972). Bursting with protest energy, Rupin’s pictures of male bathhouse scenes were an act of defiance.

© Juri Rupin. The Sauna, 1972

The shoot for Eugeny Pavlov’s series The Violin, made earlier in the same 1972, was a challenge against the aesthetics of the Soviet Photo magazine, with their law of beautiful (i.e. emasculated) subject matter surrounded by beautiful (i.e. rectified) scenery. The origins of this work are legendary. At a young hippies’ gathering, Pavlov suggested that it would be “pretty cool” to take a picture of a naked man standing in water and playing an accordion. The guys, adventurous spirits that they were, said they had a violin. None of them, not even the author himself, realized they were arranging what would become perhaps the first ever Ukrainian happening. But the situation felt totally natural to that bunch of young Beatles and Stones fans. Maybe that is the key to the cathartic chain reaction that takes hold of the flower kids “following the sun.” Here, though, the sun is setting. The mood resonates with the people and the nature, and one can almost feel it looking at the sunset halos enveloping the figures in the last few photos. This series is especially effective in its entire scope, including the marginalia. It reads like a report from an area of spontaneous collective unconscious localized in space and time.

© Eugeny Pavlov. The Violin, 1972

Almost every shot in the series contains the violin. The violin is the key to decoding the primary message of the whole act. Juxtaposing an instrument of art with the broad expanse of reality – the one inside as well as the one outside – serves to underscore, if not their total incompatibility, then at least the futility of ever hoping to capture or express it.

This conceptual statement makes sense within the context of Ukraine’s history. Nineteen-seventy-two signaled a turning point after the Khrushchev Thaw. Petro Shelest, the relatively liberal First Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine was replaced by Volodymyr Shcherbytsky, a fierce Moscow loyalist. The nascent Ukrainian hippie movement was swiftly crushed. In 1973, Pavlov’s Violin was published in Polish Fotografia magazine (#1, p.10-11) with commentary by Jan Sunderland. But when Pavlov, by that time a student of photography at the University of Theater, Cinema and TV, showed the series to his tutor, his superior said, “If I’d known you shoot such things, I’d never have admitted you into the University.” (Image above: © Eugeny Pavlov. Untitled, 1977)

Around this time Oleg Malevany created the works that first garnered international recognition. Malevany held his first personal exhibition back in the late 1960s. His role in Vremya was quite significant; his studio became a place frequented by artists, models and other bohemian Kharkovites. More so than any of the other group members, Malevany was interested in exploring the expressive potential of color. His color solarizations, posterizations, and other experimental photochemistry techniques, heralded a color revolution in Ukrainian photography of the 1970s.

The serial format has always been conceptually important in Kharkiv photography, representing a parallel sequence as an autonomous structural unit, which is typically long, well-developed, and self-contained, thus transcending the boundaries of what is perceived as the norm. One reason for this may have been a desire to create an imaginary world. The bulk of work done by Oleg Malevany, Eugeny Pavlov and Boris Mikhailov during the 1970s–1980s consists of slides of the type now commonly referred to as “overlays” or “superimpositions.” This technique probably owes much of its popularity with Kharkiv photographers of the period to its ability to conceal and transform, as well as its obvious surrealist effect. All this was perfectly in line with both the critical ideas, the style, and the imagery favored by Kharkiv photographers. This approach would later be applied even to “straight” photography, intensifying the artists’ coloristic vision.

(Above Image: © Eugeny Pavlov. Selfportrait, 1976)

Malevany’s “overlays” involve a special kind of montage—one based not so much on subject/object juxtaposition (as, for instance, in works by Boris Mikhailov), but rather on the interplay of colors. In Malevany’s photos, color represents a distinctly symbolic concept, whereby the very introduction of hue begets a separate narrative pane that describes a parallel world. Of the entire specter, red always has pride of place. Overlaid with blots of color, photographic images seem to acquire multiple layers that twist perspective and suggest motion. But this veil of color plays a much more important role in Malevany’s works: it imbues them with symbolism. Almost without exception, the color is symbolic. This approach is epitomized in The Red Meditation (1987), an eight-shot series that adds red to the usual chromatic range of color photography. Malevany’s chromatic veils are certainly abstract, but there is more to them than that: the colored shapes echo the suprematist and spectralist typology of the early Ukrainian avant-garde. In his landscape photos, the Ukrainian flora itself is presented as a multicolored palette. Thus, a meadow in bloom, thistle and milfoil blossoms poking out of thick gray wheatgrass and clover, is transformed into an abstract painting.

Malevany’s “overlays” involve a special kind of montage—one based not so much on subject/object juxtaposition (as, for instance, in works by Boris Mikhailov), but rather on the interplay of colors. In Malevany’s photos, color represents a distinctly symbolic concept, whereby the very introduction of hue begets a separate narrative pane that describes a parallel world. Of the entire specter, red always has pride of place. Overlaid with blots of color, photographic images seem to acquire multiple layers that twist perspective and suggest motion. But this veil of color plays a much more important role in Malevany’s works: it imbues them with symbolism. Almost without exception, the color is symbolic. This approach is epitomized in The Red Meditation (1987), an eight-shot series that adds red to the usual chromatic range of color photography. Malevany’s chromatic veils are certainly abstract, but there is more to them than that: the colored shapes echo the suprematist and spectralist typology of the early Ukrainian avant-garde. In his landscape photos, the Ukrainian flora itself is presented as a multicolored palette. Thus, a meadow in bloom, thistle and milfoil blossoms poking out of thick gray wheatgrass and clover, is transformed into an abstract painting.

(Image: © Oleg Malevany. Expectation, 1971)

© Oleg Malevany. No, 1969

In his multiple-exposure images, where different color-filters were used for different exposures, Oleg Malevany transforms humdrum reality into a fantastic light show. Color accents appear as a manifestation of the supernatural, dazzling the viewer with inconceivable sunrises and sunsets, illusions and mirages. Red and purple hazes, so fluidly natural they seem to belie the use of color filters, change familiar images into something fictional. The form, when intensified with color, serves to create the artistic effect of a nearly-abstract, vibrating picture. The fragmentation of the image reveals an unexpected similarity with the nonconformist art of the 1960s and 1970s, with its leanings toward the abstract and its structural rearrangements, when even melted snow mixed with dirt could be used to achieve the desired effect. And whereas in the 1910s Wladimir Burliuk applied a dirt “finish” to his paintings, by the end of the twentieth century this same dirt came to be seen as a valid structural detail. It is this interest toward such new structural arrangements that drove Kharkiv photographers to experiments with various techniques to transform the captured images. For Kharkiv photographers, it was a way of representing the twin topoi of Suffering and the Imaginary World, as well as a means to satisfy their curiosity for abstract and nonfigurative art and, consequently, legitimize it. (Above image: © Oleg Malevany. The Red Meditation, 1987)

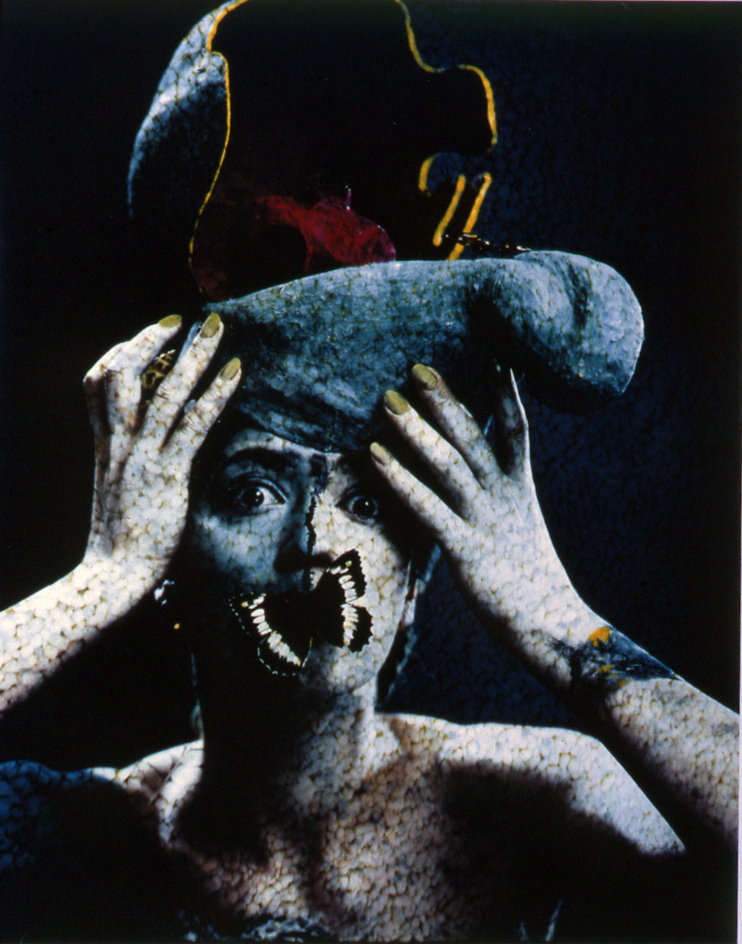

The fertile subject of blossoms informed the aesthetic aspect of Malevany’s photographic works. Here, it makes sense to draw a parallel with contemporary Western culture. Referring to the “blooming seventies,” David LaChapelle said, “I loved the photos of that time, all crazy and free from any dress codes, the imagination, the escapism.” Malevany may have been the one who introduced the idea of color intervention to the Kharkiv School. The hedonistic nature of Ukrainian art resulted in him being hypersensitive to color. In his series An Homage to Mihail Chemiakin (1993), Malevany’s passion for “beautifying the beautiful”—the female image interpreted through floral patterns being a common motive in Ukrainian art—turns a woman into a flower with a butterfly perched on top, re-imagining an ancient mimetic concept underlying the famous legend of the birds which pecked the grapes from Zeuxis’ painting.

(Image: © Oleg Malevany. An Homage to Mihail Chemiakin, 1993)

© Oleg Malevany. The Red Meditation, 1987

© Oleg Malevany. The Red Meditation, 1987

Malevany’s most famous 1970s creation is the black and white series Gravity (1975). For many, it had the effect of a bombshell: through his use of photomontage, Malevany was pushing photography into the realms traditionally occupied by painting and drawing.

© Oleg Malevany. Gravity, 1975

Despite the inevitable erotic elements, typical for Kharkiv photography of the period, Gravity’s main theme was centered on the eschatological nature of nuclear threat, a globally shared concern at the time. This was conveyed through fanciful imagery which somehow paralleled Andy Warhol’s photographic trips in its unconventional topography (for instance, accentuating manhole covers). A vague sense of an impending environmental or nuclear disaster – again, a pivotal nonconformist subject of the era – pervaded Malevany’s soon-to-be internationally renowned photo collages.

© Eugeny Pavlov. Love, 1976

Eugeny Pavlov’s 1976 Love series shares a similarly disturbing symbolism. The black and white part of the series, created in Kyiv, with its abandoned quarry and its skyline of barracks, is close to the landscapes produced in the same period (1968–1976) by members of Moscow’s Lianozovo Group (such as Oskar Rabin), seeming to share with them what Victor Tupitsyn called “barracks metaphysics.”

The second half of Love is in color and was also shot in Kyiv. Here, the topography’s most distinguishing and arresting feature is a flooded tunnel. The tunnel has a special meaning within the series, its twin straightforward/mystical connotations of technological achievement and the final journey to the underworld perfectly framing the dualistic nature of the imagery. The climactic polarization of the male and the female as a way toward the highest erotic tension is projected onto the crude urban reality of the tunnel, its militarized architecture a silent reminder of the fall from grace. The crumbling concrete walls studded with rusted rebar bring to mind the local legend of the train loaded with munitions supposedly sitting on the tracks at the bottom of the tunnel. These coarse textures look jarring against the soft grass and vulnerably nude human bodies, whose pained gestures are reminiscent of Masaccio’s Expulsion from the Garden of Eden. This railway line, built before the war and abandoned in 1948, runs through one of the darkest periods in Ukrainian history – war preparations, years of actual war, years of postwar desolation, all punctuated by repressions. The tunnel was built by prisoners. Pavlov would return to this taboo subject in 1978 with Tomorrow, a documentary film about the prison camp where the cult Ukrainian film director Sergei Parajanov was incarcerated at the time.

(Image: © Eugeny Pavlov. Love, 1976)

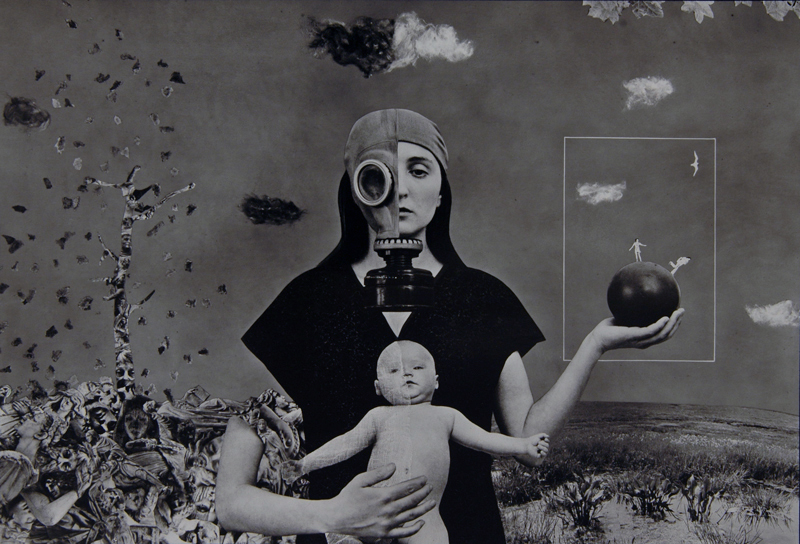

The 1980s saw Eugeny Pavlov turn to montaging experiments, the first of which, The Environmental Dream (1984), was also eschatological in nature. In 1985, a year before the Chernobyl disaster, he created the collage Alternative: an extraterrestrial artist’s-eye view of the universe overlaid with a deliberately clear image of the life-giving female. This image is divided into opposing halves, a natural scene versus a post-apocalyptic landscape. Through the fabric of the imagery one can discern the Tree of Knowledge and the Tree of Life, implying a reversal of the fall of man, offering a fall back into grace, the living world triumphing over the dead one.

© Eugeny Pavlov, The Alternative, 1985

© Eugeny Pavlov. Alone by myself, 1986

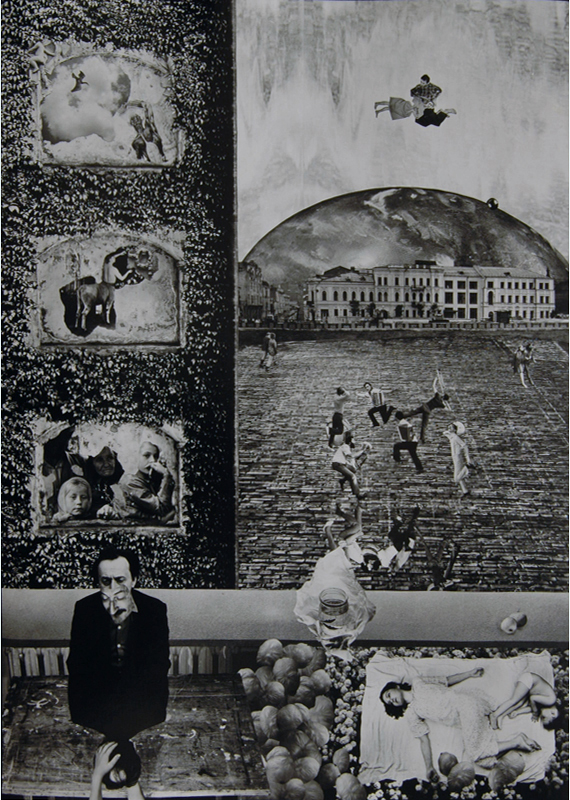

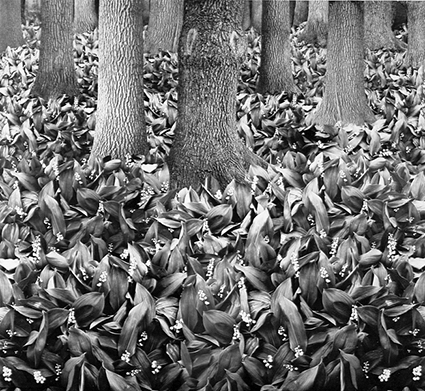

Alexandr Suprun made photomontage his artistic specialty. His images of the 1970s are still well-known in Ukraine and abroad, with Springtime in the Forest (1975) perhaps the most famous. Despite the apparently realistic image that looks almost like a snapshot, what we are looking at here is photomontage. This image harks back to the uniquely Baroque style of trompe-l’œil. Rediscovering the Baroque aesthetics was a popular trend among early-seventies artists, so it is hardly surprising the Ukrainian photographer picked up on it. Alexamdr Suprun felt right at home with its highly dramatized, sometimes downright hyperbolic imagery. Montage, too, proved to be a perfect technique for creating a richly textured, nearly hypnotic likeness of a forest clearing overgrown with lilies-of-the-valley.

Should we choose to “dig deeper” into the forest imagery, we may discover a clear environmental message. The woodsy idyll which transports us to Nature’s golden age is in fact a manmade lab project. In this artificially assembled landscape, not only are the lilies urban-grown, but even the trees were photographed in a city park. So what does the collage technique mean in terms of the artist’s message and how it is perceived? As realistic as this “nature scene” might appear, the nature here has been severely tampered with: the flowers are multiplied through mirrored images stretching out into eternity (the collage contains 51 instances of the same flower pattern). Another hint of the artificiality (which only a professional photographer can fully appreciate) is its use of split levels. The lilies are magnified, as if we are seeing them in close-up, while the tree trunks are at eye level. The trees stand in wedge-shaped formation pointing at the exact center of the frame – yet again employing a Baroque principle of intersecting diagonals. However, for all their tumultuous sensuality, even the ever-present elements of the Ukrainian Baroque are obscured by the technical aspect of collage. (Above image: © Alexandr Suprun. Springtime in the Forest, 1975)

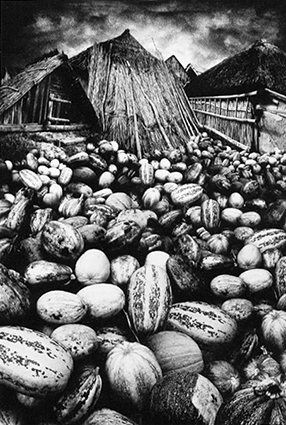

© Alexandr Suprun. The Melons, 1985

© Alexandr Suprun. The Gifts of Autumn, 1975

The mirrored symmetry, the multiple flower patterns – all this reflects upon the idea of artificial transformation of nature, foreshadowing the concept of genetic cloning. The image’s inherent conflict lies in the blurring of lines between the natural and the manmade, the wild and the technocratic, and it is a testament to the author’s talent that the collage seems imbued with some kind of magic. It is the photographic equivalent of that late-sixties motto about making “love not war,” although the Soviet underground community did away with “love” and had to be content with a vague sense of hope awakened by the Khrushchev Thaw. Still, it can be argued that they were a part of the same global context that included the hippies and the Greenpeace movement; how else to account for the lasting popularity of Suprun’s Springtime throughout the 1970s and ’80s?

© Anatoly Makienko. Autumn around My House, 1987

In 1974, Vremya was joined by Anatoly Makienko (a year later, his pictures were published by the Polish Fotografie magazine). At the time, photographics were all the rage. However, he was reluctant “to destroy the plasticity of the tonal image with the unequivocal black-and-white planes,” so his interest in this technique was short-lived. The only special method of printing that Makienko used was detail filtering, which enabled him to retain tonal separation and at the same time emphasize the contemplative restraint typical of his shots.

© Anatoly Makienko. Autumn around My House, 1987

© Anatoly Makienko. Autumn around My House, 1987

Another characteristic aspect of Makienko’s work is the blending of urban and idyllic poetics, while his subject matter is a typical city environment, popular with the Vremya collective. Most pictures show the realities of the Kharkiv Tractor Plant housing development, where the author has lived his whole life. The gigantic Constructivist development was supposed to be a prototype for a Communist “residential machine.” Once Kharkiv ceased being a capital of the Soviet Ukraine in the 1930s, the “Tractor City” quickly degenerated into a zone of entropy and an environmental nightmare. But it is exactly the neighborhood’s abandonment that becomes the subject of Makienko’s photos. Interestingly, the photographer’s wife says he still stops and takes out his camera in the same exact spots. For Kharkiv photography, shooting the mundane was no longer taboo. It can be argued that such an interest in ordinary subjects bespoke a hidden, subconscious drift toward Pop Art, also typical of this generation.

The 1987 series The Pillars set a lofty goal of “repairing the outside from the inside.” Later Makienko used artificial coloring in his photos. The 1989 Autumn, colored with dry watercolors, finds an overall unifying motive in geometry. Makienko’s output represents the utopic faction of Vremya (O. Malevany was another representative). Thus, in his later works Makienko seeks to create composition in an “uncomposed environment,” as presented by the local urban landscape. The photographer speaks of trans-subjective reality based on the internal relations between the object and the observer. He rejects narrative motivation, arranging the space in a “multicomposition,” whereby various parts are joined by meditative connections. (Image above: © Anatoly Makienko. The Pillars, 1987)

A lot of Makienko’s shots were taken “out of the window,” mostly at night. Similarly, shots from a moving train represent the concept of “eclipse.” In this case, when shots are taken with a very long exposure, the objects in the foreground become blurred, while those in the background remain clear, which contributes to a uniquely photographic visual effect. In terms of spatial movement, it is similar to “car photography,” although a photographer riding a train or a bus sees the landscape from a higher vantage point. This expands the range and volume of urban space, as seen, for example, in Jury Rupin’s series The Kharkiv Tram, which is effectively a dynamic piece, almost a performance, compared to the static imagery of Makienko’s “car photos.” (Image: © Jury Rupin. The Kharkiv Tram, 1972)

A lot of Makienko’s shots were taken “out of the window,” mostly at night. Similarly, shots from a moving train represent the concept of “eclipse.” In this case, when shots are taken with a very long exposure, the objects in the foreground become blurred, while those in the background remain clear, which contributes to a uniquely photographic visual effect. In terms of spatial movement, it is similar to “car photography,” although a photographer riding a train or a bus sees the landscape from a higher vantage point. This expands the range and volume of urban space, as seen, for example, in Jury Rupin’s series The Kharkiv Tram, which is effectively a dynamic piece, almost a performance, compared to the static imagery of Makienko’s “car photos.” (Image: © Jury Rupin. The Kharkiv Tram, 1972)

The early 1980s also saw artists turn to another important subject. Boris Mikhailov’s Berdyansk (1980) and Salt Lakes (1986) series were the first ever environmental “reports” for Kharkiv photography. People bathing in salt lakes with no organized swimming facilities look strange, almost hysterical. The urbanized setting, swimming paraphernalia, and the stark mechanical shapes look as odd as that famous World War Two picture of American sailors swimming in a bomb crater on Okinawa. This analogy brings to light an important historical factor of Mikhailov’s biography: he grew up amid the postwar chaos. Childhood impressions, forced deep into unconsciousness, have become a kind of filter, affecting anything seen with the eye. This filter enabled Mikhailov to dispense with rose-colored glasses and see the commonplace Soviet entropy for what it was, taking photographs of it even under the very tangible threat of criminal prosecution.

© Boris Mikhailov, Salt Lakes, 1986

In Salt Lakes, as in some other works by Mikhailov, photogeny is achieved wherever there is a contrast between euphoric hysteria and chaotic ruin. This juxtaposition represents the emotional context of the Stalin era, the agitation of the first postwar years. People pose next to an open pipe emerging from the water. The industrial—rather than recreational—context is the inadequacy that highlights the absurdity of the scene. On the other hand, it is also rich in “Diogenic” semantics. Here, the concept of “Diogenes” as a type of person who stands his or her own ground in defiance of political or societal norms represents the nonconformity of the 1980s. In classical art, “landscapes with Diogenes” epitomized the idea of a free and harmonic personality. These connotations are essential in understanding the significance of Salt Lakes.

According to Boris Mikhailov, at this early stage the Vremya group functioned “as one person, sharing a common hero, a dropout who felt divorced from the social machinery.” This period explored the feelings of a person who suddenly realizes he or she is a stranger in the Soviet social paradise but stubbornly carries on regardless.

© Boris Mikhailov. Unfinished Dissertation, 1985

(editorial comment) This was a period of struggle for individual and personal expression of the avant-garde. The need to counter the dominate ideology, the controlling forces, steered and moved the photographers of the “Kharkiv era” to come together in a unified voice, influencing generations of future photographers. The next installment will build upon the work and ideas expressed in this essay and take the history of the Kharkiv School of Art Photography into the 1990’s.

1.No further images of Gennady Tubalev, and none of Aleksandr Sitnichenko were available for this publication.

2. It is difficult, however, to interpret Malevanny’s early works, because a lot of them perished in a fire at his studio.

3. Landkof V., Formuly tulumbasov ili pyanstvo na rassvete, Edita Gelsen, Germany, 2002, p. 75.

4. Limonov E., Molodoy negodyay, Paris, France, 1986; and Rupin J., Luriky (Samizdat, 2007), http://zhurnal.lib.ru/r/rupin_j_k/ ; Rupin J., Diary of a Photographer (Samizdat, 2008) http://zhurnal.lib.ru/r/rupin_j_k/dnevnik_fotografa-2.Shtml.

5. Barthes R.,Camera lucida, Мoscow, Russia, 1997.

© Tatiana Pavlova