Bruce Jackson: El Paso

© Bruce Jackson

© Bruce Jackson

Artist’s Statement: El Paso 2019 -- Indicator Images

In late 2011, I wanted to take a break from work that was socially fraught. I had finished work on Inside the Wire: Photographs from Texas and Arkansas Prisons (which would be published by University of Texas Press in 2013) and Diane Christian and I had finished “In this timeless time”: Living and Dying on Death Row in America (University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

I wanted to keep photographing, but I also wanted to slow down, to photograph more thoughtfully. I had shifted from film to digital several years earlier. I’d come home from photographing with far more shots than in the film days. Too often, I was finding what I wanted looking at the images in Lightroom rather than looking and thinking about what was happening before my eyes in real time.

My son Michael mentioned this to a friend who owned a ranch about sixty miles east of El Paso. It was about the size and shape of Manhattan. He said, “If that’s what Bruce is looking for, he’ll find it here.”

He was right. After that first trip to the ranch in near Candelaria Ghost Town in December 2011, I made four more trips to the northern Chihuahuan. Two were to the Big Bend area in southern Texas; another was a rambling trip from Albuquerque through a good piece of southeastern New Mexico, then from the Guadaloupe Mountains in Texas to El Paso for the plane home.

I was planning to turn all this into a book about the desert. I had previously worked in the Arctic and I was very much aware how much people who hadn’t been to such places tended to homogenize them in their imagination: the Arctic was ice, right? Well, yeah, there’s ice; there is also a great deal more. The same with desert. Where I live, in the U.S. Northeast, people think of “desert” as something with a lot of sand and an occasional road and rest stop: the Sahara or Death Valley, perhaps with signs saying “Burger King, 35 miles.”

Deserts are, of course, very much more complex and various than that. They include spaces where things grow rarely or only at certain brief times of year (but those times can be magnificent). If they contain mountain ranges—as does the Chihuahuan—they may include dense woodlands; they consist of space where water is almost never seen, and oases where it is never absent. And deserts as huge as the Chihuahuan also contain cities.

Which I had missed in my first four trips: I hadn’t photographed a city within the Chihuahuan Desert. So in 2019, Michael and I made a fifth trip, this one to El Paso, in the southwest corner of Texas, bordering on Mexico to the south and New Mexico to the west.

Many deserts have what botanists call “indicator plants”: a plant found in that desert and nowhere else. For the Chihuahuan, the largest desert in North America—it extends from northern Mexico to much of west Texas, the lower Rio Grande and Pecos Valleys in New Mexico, and southeastern Arizona—that plant is Lechuguilla (Agave Lechuguilla). Every place I went in that desert, except the mountain forests, I saw the distinctive cluster and occasional single stalk Lechuguilla, which flowers once in its lifetime, then dies.

I’ve come to think that cities have visual equivalents of that: you see a photo and immediately you know where it was taken.. Not just obvious structures—the Brooklyn Bridge or Golden Gate Bridge, the Kremlin, the Acropolis, the Berlin Wall, the Eiffel Tower, Big Ben, Ponte Vecchio, the St. Louis Arch, the San Francisco cable cars—but something more grounded in or essential to the place as a whole.

For me, in that trip, there were three indicators for El Paso: two of them the marks of U.S. immigration paranoia on the border: the scar of Trump’s steel wall slashing through the desert on either side of and through the city and the concertina barb wire along the border and surrounding U.S. detention centers, and the murals, particularly the murals in the Secundo Barrio.

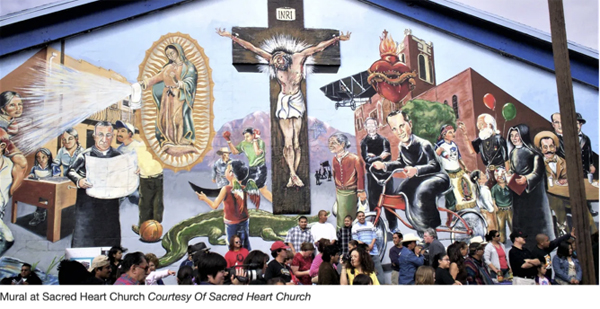

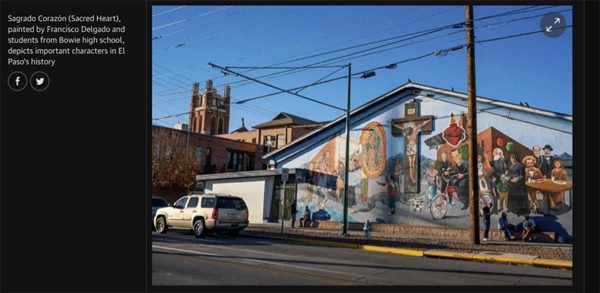

Public murals are very much in fashion in the northern U.S. these days. Mural Arts Philadelphia has produced more than 4,000 murals to cover graffiti and decorate blank walls. Town councils and public organizations commission them, as do neighborhood associations and art galleries. But the murals in Secundo Barrio have deeper roots than any murals I’ve seen in the north. They’re not current public art fashion. They are grounded in a deep Mexican mural tradition: think Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. The tradition is much older than that: it existed in Olmec Mexico, well before the Christian Era. Some of the El Paso murals are as bright and sharp as the day they were completed; others show the effects of time and weather and the mischief of graffiti taggers. Whatever their condition, the murals in Secundo Barrio feel embedded; the murals elsewhere in the U.S. seem applied.

Whatever their condition, the murals in Secundo Barrio

feel embedded; the murals elsewhere in the U.S. seem applied.

Some of the El Paso murals are community projects. Of the most striking is a wall depicting much of San Antonio’s history done over a summer by a high school class. It includes a beloved local priest, Harold Rahm, who traveled by bicycle. Rahm was in El Paso for 12 years, then he was sent to Bolivia; when he retired decades later, he returned to El Paso, where he died at 100. I saw him in two other murals, pedaling away. Some of the murals result from a store owner thinking “I need this for my store.” Some seem like work by graffiti artists struck by larger inspiration. No simple description of style or technique comes close to the variety of what you see on a thirty minute drive.

Here in the exhibition is a sampling of that gift to the street. But first the concertina razor wire at the point on the pedestrian path of the Ysleta-Zaragosa International Bridge where you step from Mexico into the United States and at a refugee detention center, then then some photos of Donald Trump’s barrier wall (in Secundo Barrio and the desert to the west) which has done nothing to solve the refugee problems, but which has done great harm to animal life on both sides of the U.S./Mexican border. The murals, the wire and the wall: Beauty and the Beasts.

© Bruce Jackson

© Bruce Jackson

Detail of school wall.