Larry Chatman

© Larry Chatman

© Larry Chatman

The Bar and Where "we" Live

Curator: Roberto Muffoletto

Documentary photography has a long and dynamic history ranging from what appeared to be the product of a neutral machine with an operator recording the existence of objects, people and events to the subjective historically and culturally based notation.

In the late 20th century there was the emergence of the “new documentary”. The border between documentary (which includes photojournalism) and the new documentary (at times is referred to as social documentary) is the recognized subjective historical nature of the image and the photographer. Framed as an author, a decision-maker and not as a neutral observer recording the decisive moment before them. (A counter theory to the “decisive moment” put forth by Herri Cartier-Bresson is the “moment of decision” coined by Nathan Lyons. The “decisive moment” requires the photographer to recognize the moment when the form and meaning emerge in the external world. The “moment of decision” refers to the internal subjective nature of the photographer and what they respond to in the external world. In this case the photographers is active and the produced images reflects the interest and decisions of the image-maker.) New documentary breaks from the empirical notion of image making as an objective behavior, non-political, economic or historical decision. This also mirrors the paradigmatic shift from modernism to post-modernism, empirical to qualitative, objectivity to subjectivity and the TRUTH to truths. The camera (which is not a neutral object) records the space in front of its lens, it is the photographer who decides where to “stand” and when to “click” the shutter. It is the photographer who makes the decision.

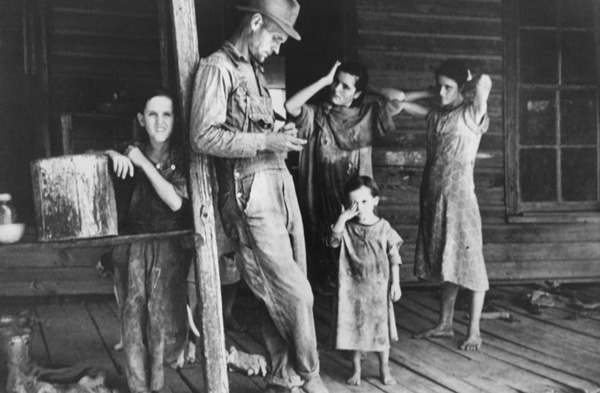

New documentary photography goes beyond the appearance of being ideologically neutral to a subjective stance. The work of Jacob Riis (who used his camera to record the poor and disenfranchised of New York City (1880-1910), the documentary work of the (USA) Farm Security Administration project (1930s) and later the 1975 George Eastman House exhibition entitled “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape”, placed the notational aspect of the photographic act within the social landscape and the human condition. (Image right: Walker Evens, LOC collection)

New documentary photography goes beyond the appearance of being ideologically neutral to a subjective stance. The work of Jacob Riis (who used his camera to record the poor and disenfranchised of New York City (1880-1910), the documentary work of the (USA) Farm Security Administration project (1930s) and later the 1975 George Eastman House exhibition entitled “New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape”, placed the notational aspect of the photographic act within the social landscape and the human condition. (Image right: Walker Evens, LOC collection)

Photographers address the human condition through images and text not only to record it, but to “point to it” in the hope of bringing attention to the certain social condition whether it be the poor and disadvantaged or the comfortable and powerful. The photographer as witness, a witness with a purpose and a point of view, builds upon a visual language, a cultural code, to be read from various perspectives, contexts and histories. It is here that I place Larry Chatman’s work exhibited here – The Bar and Where “we” Live.

In both cases Chatman provides us with videotexts – his story – to locate his images within his own history and a social political economic paradigm.

To the visiting eye The Bar may first appear as snapshots (or participant performances for the camera) that could be found in FaceBook, in a hanging picture frame at home or on the wall of a local pub. “This is me, this is where I spend my social time and these are the people who come here.” This could be the case for those imaged and may reflect normalization, similar to photographs of people living a suburban context: all appears normal. I am with others like myself.

To the visiting eye The Bar may first appear as snapshots (or participant performances for the camera) that could be found in FaceBook, in a hanging picture frame at home or on the wall of a local pub. “This is me, this is where I spend my social time and these are the people who come here.” This could be the case for those imaged and may reflect normalization, similar to photographs of people living a suburban context: all appears normal. I am with others like myself.

This is not to suggest that the poor and working poor do not recognize their situation. They have social mirrors and windows, billboards and advertisements that refer to a better material life. It is a life where everyone appears to be happy, a life different from theirs – they have to go home.

Where “we” Live is Chatman’s personal voyage to his past, his memories of his youth, the place where he grew up and his home. (How many of us have made that journey only to find a different place, not our home.)

Where “we” Live doubles as a political statement concerning institutional racism and the struggle for a better life. As Chatman points his camera he indicts the practices of white America. From redlining to segregated schools, the development of housing projects and later on the growing black middle class and their migration into white suburbs.

As with any image, meanings are elusive without a context or frame. To look at the work of Jacob Riis, Andrezej Baturo, Boris Mikhailov or Leonardo Carrato without seeing their images within an historical and social framework is to see them only as images, meaningless images. For meaning emerges from the conversation between the reader/viewer, the image and the social political context of the reading experience. For me this is the dilemma of postmodernism and the new documentary, there is no fixed meaning, no absolute truth and no single history. Truth is a product of time, language and perception.

Taken as a whole this exhibition is not the work of a voyeur or a pedestrian but the work of a committed image maker working through his own questions concerning his life. In reference to his videotexts, Chatman takes us into a world that he could have lived and to a memory that is incomplete.

© Roberto Muffoletto 2016