Patricia Aridjis: las horas bnegras

© Patricia Aridjis

© Patricia Aridjis

las horas negras

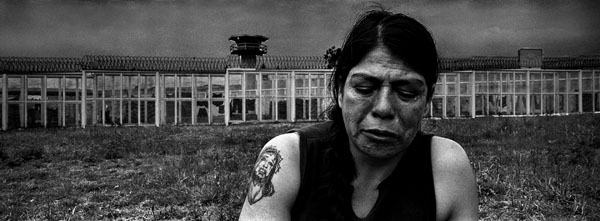

The “Las horas negras” (The dark hours) VASA exhibition and book by Patricia Aridjis provides us with a view or (visual) text of a woman’s prison in Mexico. Aridjis’s work presents a number of challenges to the interested viewer, requiring empathy and objectivity, and possibly a paradigm shift concerning those in prison.

Over the years photographers have gained access to other worlds, not just prisons, but gangs, racist organizations (another form of gang), religious groups and private places (private places are no longer private once photographed and published). For most of us, our understandings of these “other” worlds flow through the gates of the media, popular film, and reporting. (image left: Danny Lyons "The Bike Riders", 1968: Google search result 20 March 2016)

Over the years photographers have gained access to other worlds, not just prisons, but gangs, racist organizations (another form of gang), religious groups and private places (private places are no longer private once photographed and published). For most of us, our understandings of these “other” worlds flow through the gates of the media, popular film, and reporting. (image left: Danny Lyons "The Bike Riders", 1968: Google search result 20 March 2016)

As we experience information on either the rich and famous, or the down and out, our thoughts are mediated and guided  by previous knowledge (or partial knowledge) of such places and people. We cannot forget that places found outside our window, are structured and maintained by an ideological framework, a political and economic agenda, normalized as a taken-for-granted history. After all, we are looking out a window. We understand the world and ourselves in it because of our constructed mediated history. We have no choice in an historical world constructed for us. We are either an outsider or an insider, framing our understanding of the other as different. Inquires into our social world may challenge our relationship to others and impacting our own identity. The work of Patricia Aridjis presented here in VASA Exhibitions may do just that. She guides us through a space, introducing us to others in a manner that may impact and challenge our assumptions and understandings. (above image: Bruce Jackson, 1973, from the book "Killing Time: Life in the Arkansas Penitentiary", with permission)

by previous knowledge (or partial knowledge) of such places and people. We cannot forget that places found outside our window, are structured and maintained by an ideological framework, a political and economic agenda, normalized as a taken-for-granted history. After all, we are looking out a window. We understand the world and ourselves in it because of our constructed mediated history. We have no choice in an historical world constructed for us. We are either an outsider or an insider, framing our understanding of the other as different. Inquires into our social world may challenge our relationship to others and impacting our own identity. The work of Patricia Aridjis presented here in VASA Exhibitions may do just that. She guides us through a space, introducing us to others in a manner that may impact and challenge our assumptions and understandings. (above image: Bruce Jackson, 1973, from the book "Killing Time: Life in the Arkansas Penitentiary", with permission)

It is a question of meaning and knowledge forming our understanding, expectations and behaviors towards the other.

Viewers, whether viewing photographs, paging through a book, or watching a film are able to safely stand back with gazes of voyeuristic awe or disinterest. For many of us these worlds are far outside our lived experiences and understandings. The descriptions of the world(s), as seen through the photographer’s lens, range from passionate and romantic to detachment and objectivity, from stylistic metaphors to stark realism.

The “Las horas negras” exhibition moves us past reportage and objectivity (actually no photograph is objective, photographs are social historical constructions) to a closer emotional connection to the woman depicted. The exhibition could be viewed as encyclopedic, showing us various aspect of life within the prison walls. We see woman with children, lovers and relationships, decorated cells, and a few activities outside the confines of their cells. We do not see the prison labor areas or yard activities.

There are no Madonna images found here. For the most part Ardjis’s framing is tight, bringing us in close reducing the psychological distance, creating an emotional link between the viewer and the image. Most images have the subject holding direct eye contact with her viewer (Aridjis and us), thus forming another level of emotional amd psychological connection. The emotional connection between the viewer/reader is heightened with the inclusion of children. It is one experience to think of men or fathers in prison but a mother and their children elicits a different type of response. In the end, Aridjis provides us with a softer look, one of people living their lives in an institution, a confined environment, both physical and psychological. (image: © Patricia Aridjis, from las horas negras)

There are no Madonna images found here. For the most part Ardjis’s framing is tight, bringing us in close reducing the psychological distance, creating an emotional link between the viewer and the image. Most images have the subject holding direct eye contact with her viewer (Aridjis and us), thus forming another level of emotional amd psychological connection. The emotional connection between the viewer/reader is heightened with the inclusion of children. It is one experience to think of men or fathers in prison but a mother and their children elicits a different type of response. In the end, Aridjis provides us with a softer look, one of people living their lives in an institution, a confined environment, both physical and psychological. (image: © Patricia Aridjis, from las horas negras)

Photographs and films, television documentaries and dramas on prison life are not new. A quick Google search will unearth a large number of programs on men’s and woman’s prison life. (** insert images) The texts (visual and mediated) are usually produced on sensationalism, the erotic and the violent. They are text built upon the perceived notions of prisons and those who live there – both guards and inmates. (image above: © Patricia Aridjis, from las horas negras)

Photographs and films, television documentaries and dramas on prison life are not new. A quick Google search will unearth a large number of programs on men’s and woman’s prison life. (** insert images) The texts (visual and mediated) are usually produced on sensationalism, the erotic and the violent. They are text built upon the perceived notions of prisons and those who live there – both guards and inmates. (image above: © Patricia Aridjis, from las horas negras)

Experiencing this exhibition we need to consider what have we over-looked, what we are seeing and what we are not, and why. As with any text it is written from a perspective, a possible audience in mind, and a purpose.

Image: Google search results, 20 March 2016.

© Roberto Muffoletto 2016